Phosphate found on Enceladus boosts chances for life

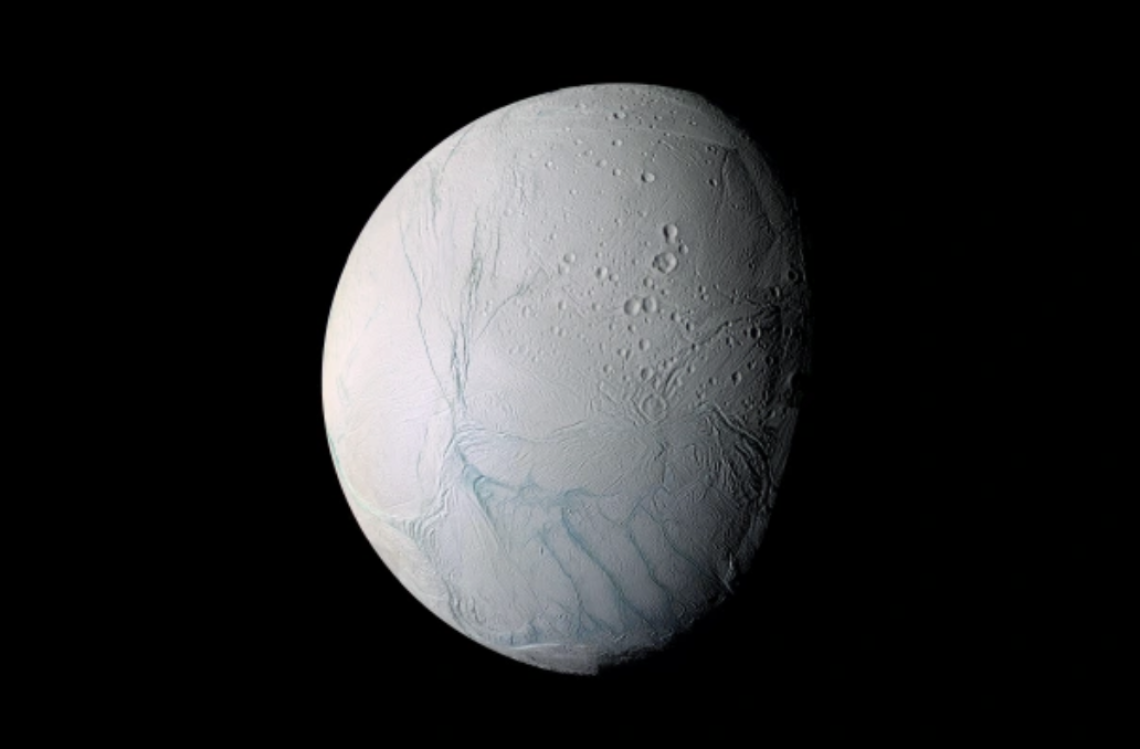

Enceladus' famous tiger stripes are visible in this mosaic taken by the Cassini spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Article by Christopher Cokinos for Astronomy.com.

According to legend, the ancient giant Enceladus vents sulfur from his tomb. According to data, Saturn’s tiny moon Enceladus vents more than that.

In a new analysis of data from the retired Cassini mission to Saturn, an international team of researchers say they have detected phosphorus — a key ingredient for life — coming from Enceladus’ subsurface warm, salty ocean. The report means scientists have found evidence at Enceladus for the six most critical elements needed for life as we know it.

Those elements are known collectively by the acronym CHNOPS: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulfur. Because phosphate is so vital to life, the fact that it had not yet been found at Enceladus was once considered a show-stopper. But now, Enceladus is the only other place in the solar system besides Earth with compelling evidence for all six, opening the door for life to potentially exist beneath the moon’s icy surface.

The study was led by Frank Postberg, a planetary scientist at the Free University of Berlin in Germany, and published June 14 in Nature.

Postberg told Astronomy that while further study is needed to determine the exact amount of phosphorus present at Enceladus, he thinks the detection is “absolutely bullet-proof.” (In fact, the weakest detection of the six CHNOPS elements at Enceladus is now sulfur.)

Even better, says Postberg, is that the phosphate found there is soluble, meaning it can dissolve in water and is therefore available to use by any possible life.

“A big deal”

Enceladus is covered by a 12-mile-thick (20 km) crust of highly reflective ice that betrays many signs of geological activity. In places, there are old impact craters, but much of the terrain is young and worked over by active ice tectonics. There are ridges, scarps, plains, groves, and troughs, and, at the south pole, four “tiger stripes” — which are fractures bordered by ridges. Some parts of this region may be as young as 500,000 years.

From these cracks, geysers of water ice stream out into space, forming a plume over the moon’s south pole that was first seen by Cassini nearly two decades ago. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) recently caught a 6,200-mile-long (10,000 km) spray ejecting nearly 80 gallons of water (300 liters) per second — enough to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in just a couple of hours.

At just 310 miles (500 kilometers) wide, Enceladus is too small to generate energy on its own. But the moon is flexed by Saturn’s gravity, providing energy for the cold, dark ocean, which could be 25 miles (40 km) deep. Beneath the ocean floor, the moon’s core seems to be unusually hot. That could mean the existence of hot hydrothermal vents like those in Earth’s oceans — and those teem with microscopic and macroscopic life.

This ocean has long been considered one of the best places to search for life in the solar system. But before this work, scientists had not yet found all of the most important ingredients for life.

Postberg says his team did not set out specifically to look for phosphates but rather, “anything new” in the Cassini data. But he realized “pretty quickly” that a mass spectrometry signal that was “previously unknown” was “probably phosphate,” though several months passed before he was fully convinced.

“That was an exciting and tantalizing moment,” Postberg said. “However, not being an astrobiologist, I … underestimated [a little bit] the significance of the finding.” It took his colleagues to tell him that this was “a big deal.”

The team found the sodium phosphate in data from Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA) — an impressive feat considering the instrument wasn’t designed for such a detection. The team boosted its signal by gathering samples from not just the plume itself but also from the E-ring, a diffuse ring of Saturn fed by the plume.

Click here to continue reading on Astronomy.com, which includes a quote from Dr. Regis Ferriere, a professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Arizona.